Disorders of the Esophagus

- related: GI

- tags: #GI

Symptoms of Esophageal Disease

Dysphagia

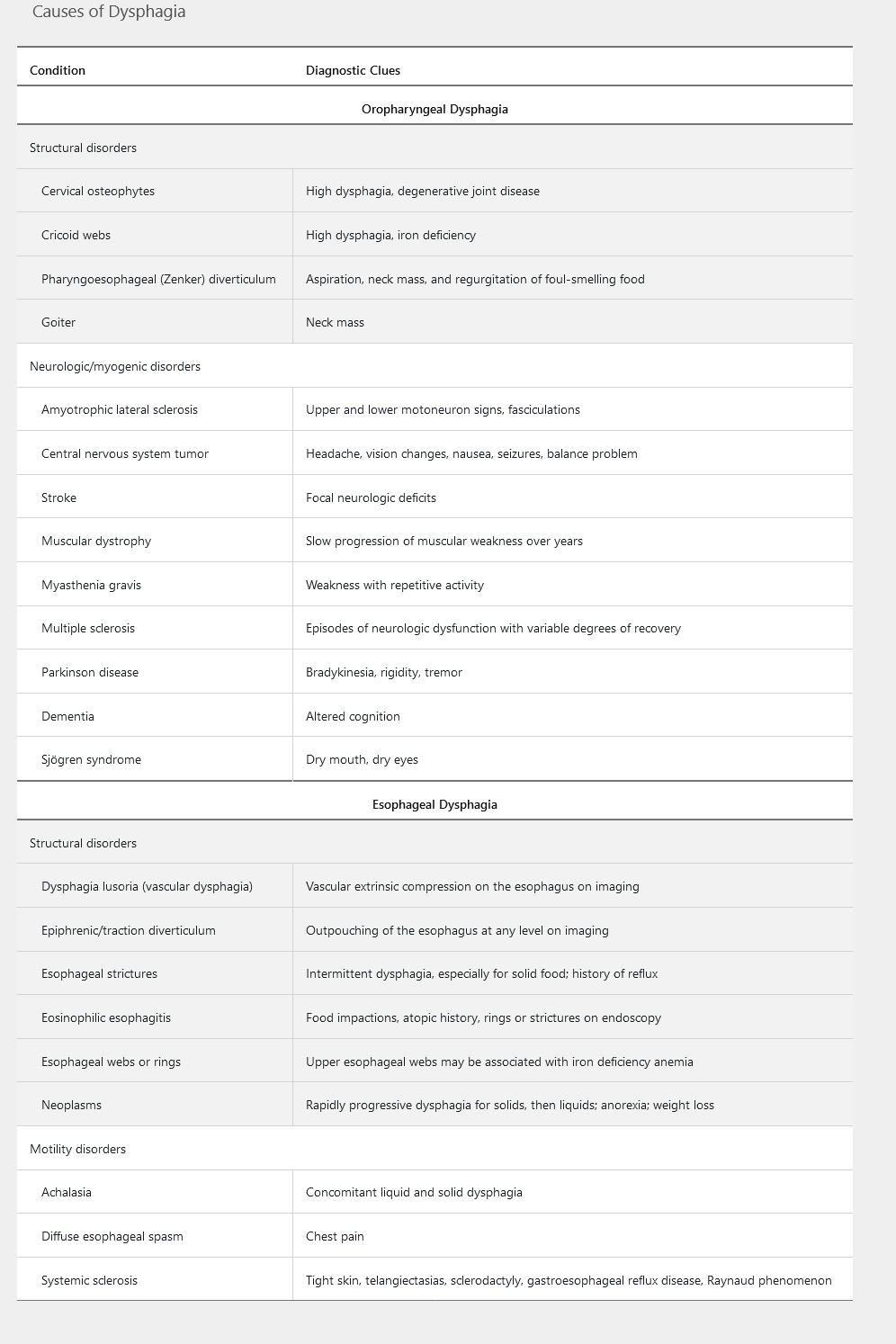

Dysphagia represents a disruption in the swallowing mechanism, resulting in food not passing from the mouth to the stomach. Common descriptions of the sensations of dysphagia include food “hanging up” or feeling “lodged” or “stuck” during a meal. Determining whether the underlying cause is oropharyngeal or esophageal is important in developing a differential diagnosis and management plan. Table 1 highlights the common causes of dysphagia.

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Oropharyngeal dysphagia, also known as transfer dysphagia, occurs when the patient is unable to transfer the food bolus from the mouth into the upper esophagus by swallowing. Symptoms commonly reported include choking, coughing, and nasal regurgitation of food. Patients are at risk for aspiration pneumonia. Other presenting symptoms include hoarseness (resulting from laryngeal nerve damage) and dysarthria (from weakness of the soft palate or pharyngeal constrictors), both representing an underlying neurologic disorder. A pharyngoesophageal (Zenker) diverticulum should be considered when undigested food is brought up several hours after a meal or if a patient reports hearing a gurgling noise in the chest. Also halitosis.

The initial study for suspected oropharyngeal dysphagia is a modified barium swallow, with both a liquid and a solid phase to help identify the underlying cause. Management strategies include dietary changes and a swallowing exercise program implemented with a speech pathologist.

Esophageal Dysphagia

Patients with esophageal dysphagia are able to initiate the swallowing process, but often feel discomfort in the mid to lower sternum as the food bolus passes through the esophagus. Esophageal dysphagia is the result of one of two underlying causes: a mechanical obstruction or a motility disorder. Dysphagia occurring with solids alone suggests a mechanical obstruction, whereas dysphagia with either liquids alone or the combination of liquids and solids favors a motility disorder. Dysphagia that progresses from occurring with solids only to occurring with both solids and liquids suggests malignancy.

Achalasia often presents with nonacidic regurgitation of undigested food. Chest pain while taking liquids that are very hot or very cold may indicate esophageal spasm. Mechanical esophageal obstruction may be benign or malignant and may be caused by strictures, masses, esophageal ring (for example, a Schatzki ring Figure 1), or webs. Upper endoscopy allows for diagnostic (biopsy and inspection) and therapeutic intervention (dilation). Clinical management is based on the underlying cause.

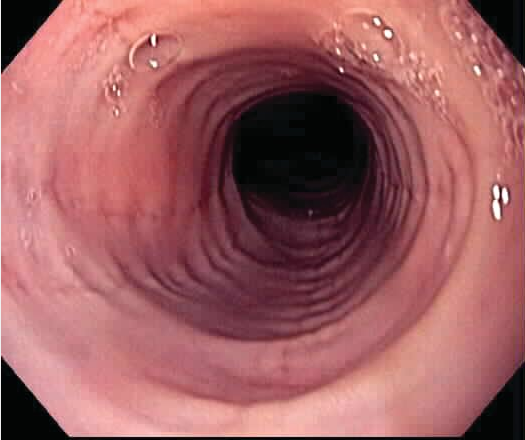

Esophageal (Schatzki) rings may be congenital or acquired (due to damage from gastroesophageal reflux) and account for 15%-30% of cases of dysphagia. Symptomatic patients frequently present with complaints of solid food dysphagia or reflux symptoms. Barium esophagram is more sensitive than endoscopy for diagnosing Schatzki rings because the rings are not easily visualized unless the lower esophagus is widely distended.

First-line treatment involves endoscopic dilation for symptomatic relief. However, many patients develop recurrent symptoms usually starting after 1 year of therapy. More than 70%-80% of patients develop recurrence within 5 years. Thus, recurrence is a rule rather than an exception in these patients. Those with recurrent symptoms are treated with repeated dilation and acid suppression (eg, proton-pump inhibitors). Some studies have shown that patients with and without reflux symptoms treated with proton-pump inhibitors have fewer recurrences of symptoms.

Barium esophagram showing a Schatzki ring, a subtype of esophageal ring located at the squamocolumnar junction and a common cause of dysphagia.

Barium esophagram showing a Schatzki ring, a subtype of esophageal ring located at the squamocolumnar junction and a common cause of dysphagia.

Reflux and Chest Pain

The development of chest pain from an esophageal cause can mimic chest pain from cardiac disease. Reports of heartburn with history of Raynaud phenomenon could signify a systemic condition, such as scleroderma.

Once a cardiac cause is ruled out, the most common cause of chest pain is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Starting a course of an acid-reducing agent, such as an H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor (PPI), can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Patients whose symptoms do not respond require further evaluation, including upper endoscopy and possibly ambulatory pH testing with or without esophageal manometry.

Odynophagia

A presentation of pain while swallowing defines odynophagia, which suggests active mucosal inflammation and ulceration in the esophagus. Odynophagia is commonly associated with pill-induced damage, infection, or caustic ingestion, and is less commonly caused by GERD or esophageal cancer. Upper endoscopy with biopsies is the most appropriate diagnostic test to determine the degree of inflammation and underlying cause.

Globus Sensation

Patients commonly report globus sensation as a “lump in the throat” or “throat tightness,” usually not linked to meals. Causes of globus include GERD (with or without heartburn), stress, and psychiatric conditions (anxiety, panic disorders, somatization). A diagnosis of globus should not be made if the patient reports other esophageal symptoms, such as dysphagia or odynophagia. Evaluation to determine the underlying cause should include evaluation for thyroid goiter and an underlying pharyngeal lesion, which can be diagnosed by transnasal endoscopy or barium swallow.

Treatment with acid suppression or cognitive behavioral therapy should be initiated once a structural cause has been ruled out.

Nonmalignant Disorders of the Esophagus

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

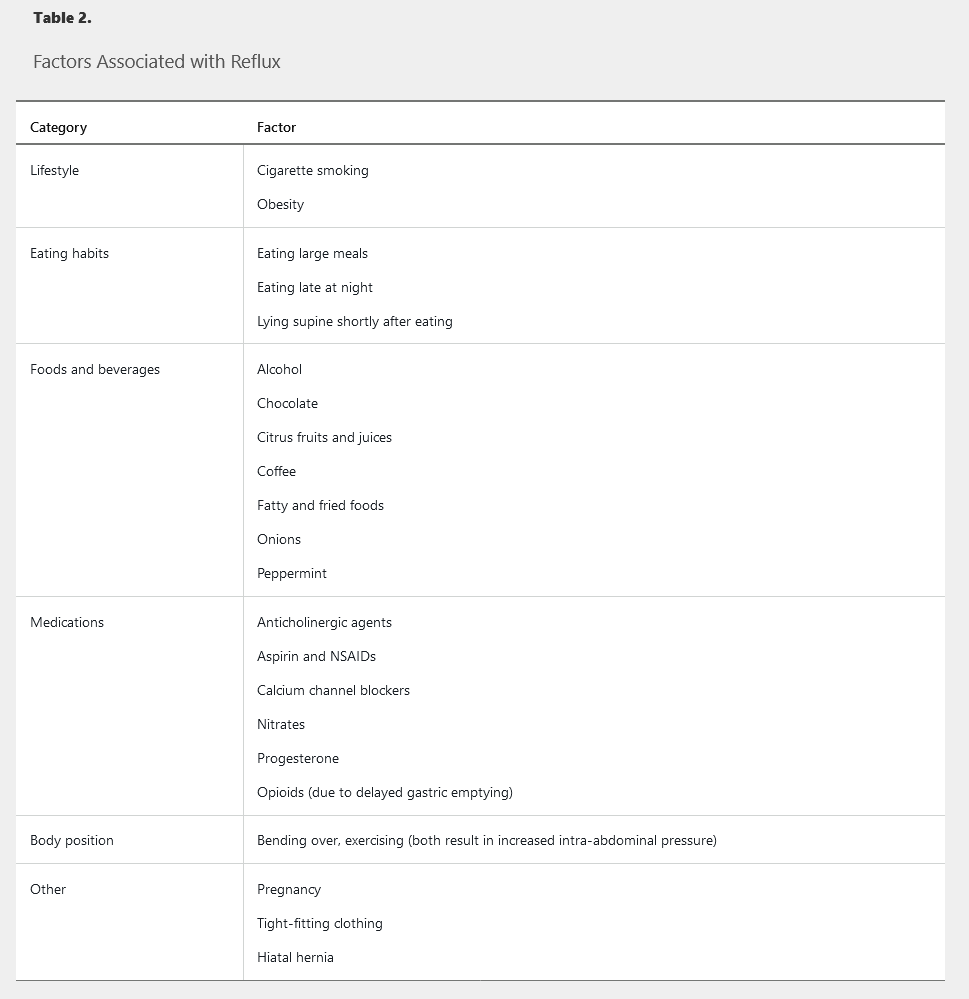

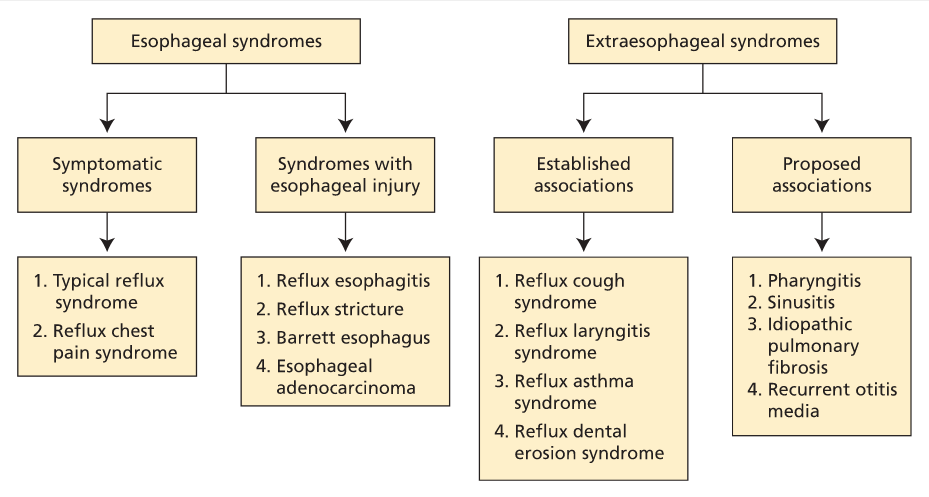

GERD is characterized by food and acid refluxing from the stomach into the esophagus and throat. Its prevalence is 10% to 20% in the Western world, and there is a strong relationship between GERD and obesity. The most common symptoms reported are heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain, for which a cardiac cause must be excluded. Reflux can be triggered by a number of factors (Table 2). Protective mechanisms to minimize the esophagus' exposure to acid consist of peristalsis, a competent lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and gastric emptying; reflux occurs when these physiologic protectors become ineffective. Uncontrolled GERD can negatively affect quality of life due to poor sleep, low productivity, and work absences. Longstanding GERD can lead to complications, including erosive esophagitis, stricture, Barrett esophagus, and esophageal cancer (Figure 2). Pregnant women may experience GERD during any trimester of pregnancy, but symptoms may worsen as the pregnancy progresses. Heartburn symptoms resolve after delivery.

Classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease and its subsets.

Classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease and its subsets.

Diagnosis

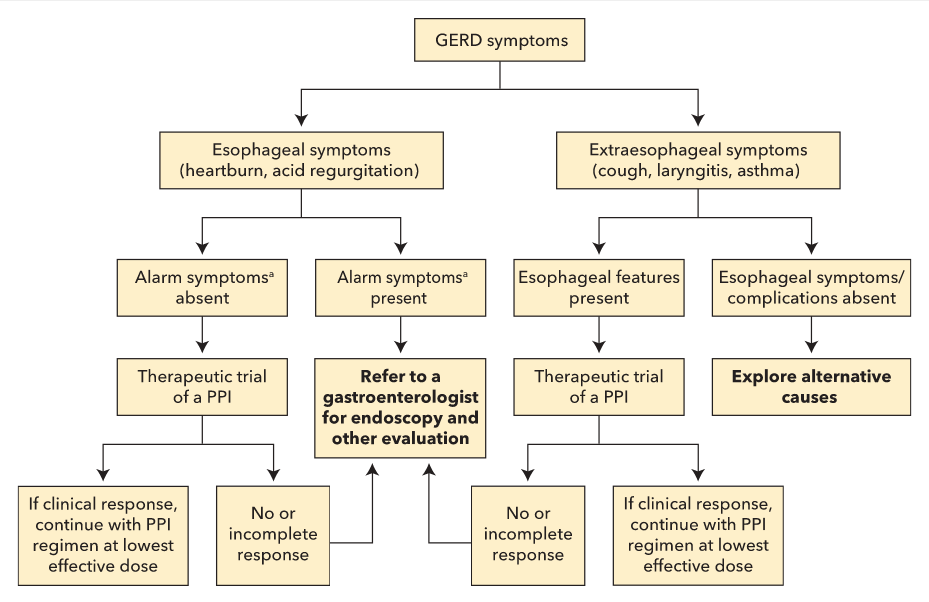

Strategies for diagnosing GERD include use of clinical history, response to medical therapy, and testing, including endoscopy and ambulatory pH monitoring; there is no single gold-standard diagnostic test. Clinical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation strongly suggest GERD. Patients with GERD symptoms, but without alarm features (such as dysphagia, unintentional weight loss, hematemesis, or melena) may undergo an empiric trial of a PPI.

Upper endoscopy is warranted in patients reporting dysphagia to rule out an underlying ring, web, or malignancy, and in patients with suspected erosive esophagitis, stricture, or Barrett esophagus. Most patients with GERD have a normal upper endoscopy examination.

Ambulatory pH monitoring can assess the degree of acid exposure in the esophagus, especially in patients unresponsive to acid-reducing therapy. Impedance-pH testing can help differentiate between acid and nonacid reflux. Testing to detect active acid reflux can be done with a 24-hour transnasal catheter or a 48-hour wireless capsule, which patients generally tolerate better. Esophageal manometry has limited value in diagnosing GERD, but should be considered as part of the evaluation for antireflux surgery to rule out motility disorders such as achalasia.

Treatment

An algorithm outlining the management of GERD is presented in Figure 3.

Lifestyle Changes

Patients with recent weight gain or overweight should develop a weight-loss plan. Patients with nocturnal GERD should eat at least 2 to 3 hours before going to sleep and should consider raising the head of the bed.

Dietary modification should focus on eliminating foods that trigger an individual patient's GERD symptoms, rather than globally eliminating all common trigger foods (caffeine, chocolate, spicy foods, acidic foods such as citrus fruits, and fatty foods). Cessation of alcohol and tobacco use is universally supported.

Medical Therapy

Pharmacologic therapy includes antacids, H2 blockers, and PPI therapy. A PPI once daily for 8 weeks is the therapy of choice for symptom relief, as well as for treatment of erosive esophagitis. PPI therapy is superior to H2 blocker therapy for GERD with or without erosive esophagitis. The PPI should be taken once daily, 30 to 60 minutes before the first meal of the day. Patients with partial response to PPI therapy should increase the dosage to twice daily. Patients requiring long-term maintenance therapy should be placed on the lowest effective PPI dose, including on-demand or intermittent usage, and for patients with uncomplicated GERD, an attempt to stop or reduce chronic PPI therapy should be made once a year. Potential adverse effects of PPIs are shown in Table 3. Switching to a different PPI may be warranted for adverse reactions or for unresponsive symptoms. Initial studies suggested an interaction with clopidogrel; however, subsequent data suggest that concurrent use does not increase risk for a cardiac event. PPIs are safe in pregnant patients.

Sucralfate has no role in the treatment of GERD. Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide should not be used to treat GERD unless gastroparesis is present.

Antireflux Surgery

Surgical treatments for GERD are laparoscopic fundoplication or bariatric surgery for obesity, as well as magnetic sphincter augmentation, a newer technique in which a magnetic ring is placed around the LES without surgical alteration of the stomach. Surgery is infrequently required; indications include failure of optimal therapy, wanting to stop medication, and intolerable medication side effects. Patients should undergo objective testing, such as impedance-pH monitoring, to confirm true acid reflux and correlation with symptoms before surgery. Surgery is most effective in patients with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation that are responsive to therapy. However, about one third of patients require resumption of a PPI 5 to 10 years after surgery. Postoperative complications include dysphagia, diarrhea, and inability to belch from a tight fundoplication.

[!NOTE] Surgery only effective for patients with good response to medicine

Endoscopic Therapy

Endoscopy-based therapies for GERD include thermal radiofrequency to augment the LES, silicone injection to the LES, and suturing of the LES. Early relief of reflux symptoms has been seen with these therapies, but long-term benefits have not been proven. None of these therapies has been associated with normalized esophageal pH levels. Newer approaches include transoral incisionless fundoplication, which is a full-thickness suture to create an endoscopic fundoplication, but there are no long-term data on its efficacy.

Extraesophageal Manifestations

Asthma, chronic cough, and laryngitis have been linked to GERD (see Figure 3). It is important to eliminate other non-GERD causes when these symptoms are present. Laryngoscopy often shows edema and erythema as signs of reflux-induced laryngitis. However, more than 80% of healthy persons also have these findings; therefore, laryngoscopy should not be used to diagnose GERD-related laryngitis. A PPI trial is recommended in patients who also have typical GERD symptoms. If a patient has atypical symptoms only, ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring should be considered before a PPI trial. Surgery is less effective in this group and should be considered only in patients whose symptoms respond to PPI therapy.

Refractory GERD

The first step in addressing refractory GERD is to optimize PPI therapy by emphasizing the importance of taking medication 30 to 60 minutes before eating, increasing the dosage to twice daily, or switching to another PPI. If symptoms are still unresponsive, alternative causes must be considered. For typical symptoms, use endoscopy to rule out eosinophilic esophagitis or erosive esophagitis. Esophageal impedance-pH testing may also be useful and should be performed while the patient is receiving optimized PPI therapy. For atypical symptoms, refer the patient to otorhinolaryngology, pulmonary, or allergy specialists to identify and treat the underlying cause. In these patients, medical therapy should be stopped before impedance-pH testing. A negative impedance-pH test likely means that the patient does not have GERD and PPI therapy should be discontinued. For patients with both types of symptoms, if further evaluation is unremarkable, impedance-pH testing should be performed.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a condition commonly associated with dysphagia and food bolus obstruction. Most patients are diagnosed between the second and fifth decades of life, and EoE is more commonly seen in men. Patients often have other atopic conditions such as asthma, rhinitis, dermatitis, and seasonal or food allergies. The reported prevalence is as high as 40 to 90 per 100,000 in the United States. The diagnostic criteria for EoE are esophageal symptoms (dysphagia), esophageal biopsies showing 15 eosinophils/hpf or greater, and exclusion of other causes of eosinophilia. Examples of other causes include GERD; hypereosinophilic syndrome; infections (fungal, viral); autoimmune and connective tissue disorders; Crohn disease with esophageal involvement; and drug hypersensitivity reactions. EoE is a diagnosis made in the absence of peripheral eosinophilia.

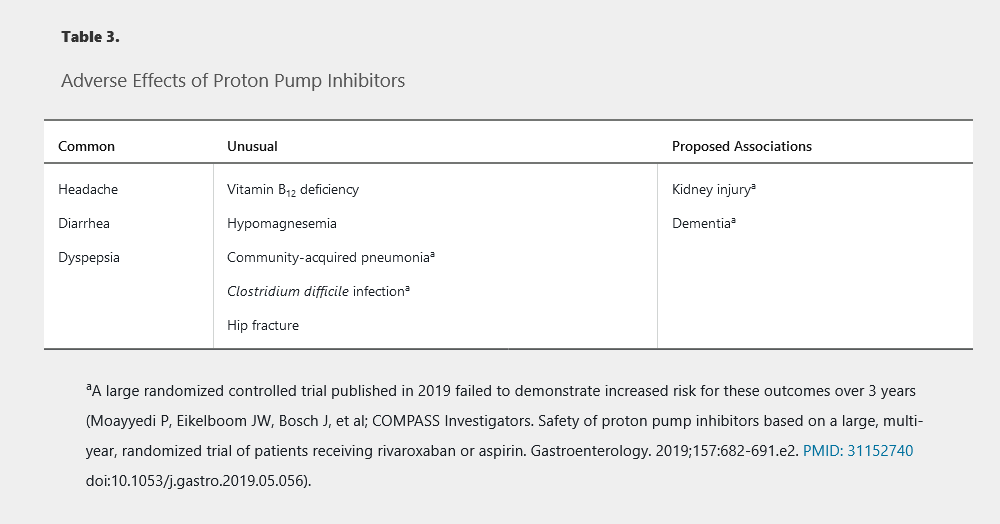

Endoscopic findings include rings, longitudinal furrows, luminal narrowing, and white exudates and plaques. If assessment identifies no other causes of eosinophilia, EoE can be diagnosed and appropriate therapy initiated, with a PPI or swallowed aerosolized topical glucocorticoids (fluticasone or budesonide). Very limited evidence suggests diet modification may be effective in the prevention of EoE. An empiric elimination diet—removing the foods most commonly associated with food allergies, such as egg, soy, wheat, peanuts, cow's milk, and fish/shellfish—and elemental amino acid–based diets have been used. Endoscopic dilation should be considered in patients with continued dysphagia caused by esophageal stricture not responding to medical therapy.

Infectious Esophagitis

Infectious esophagitis can be caused by fungal, viral, bacterial (uncommon), and parasitic pathogens. Patients most commonly present with odynophagia or dysphagia. Candida esophagitis most commonly causes dysphagia, while viral esophagitis produces odynophagia. Other organisms associated with esophagitis include Lactobacillus, B-hemolytic streptococci, Cryptosporidium, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Mycobacterium avium complex, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

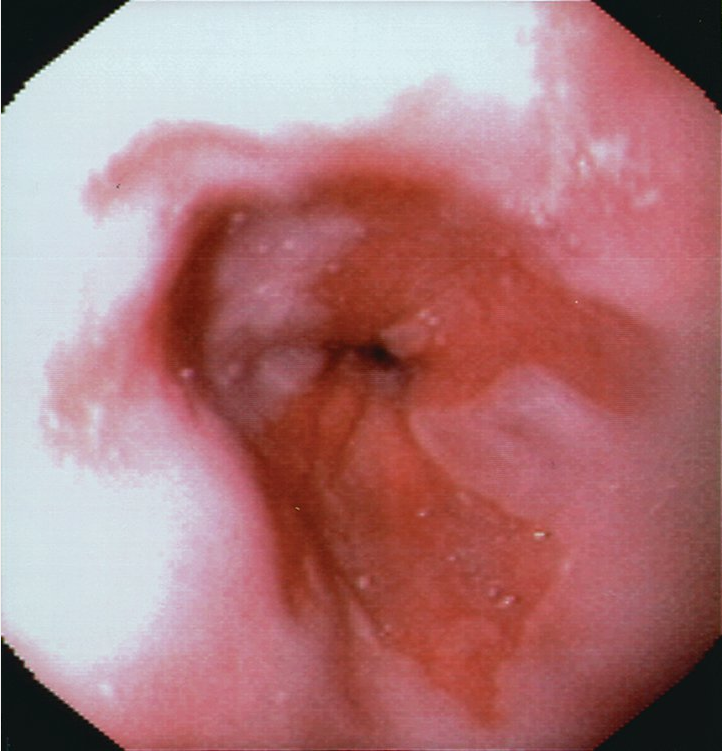

Candida infection can occur in immunocompetent or immunocompromised hosts. Diagnosis is usually made clinically based on the presence of compatible symptoms and oral candidiasis. Endoscopy and biopsy can be considered for patients who do not respond to empiric therapy or have atypical symptoms. Endoscopy shows small, white, raised plaques, and esophageal brushings confirm the diagnosis (Figure 4). The most common species is Candida albicans, treated with oral fluconazole.

Herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus are seen in immunodeficient or immunosuppressed individuals, but rarely in immunocompetent patients. Endoscopy with biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis. Herpes simplex virus infection is treated with acyclovir, and cytomegalovirus infection with ganciclovir.

Pill-Induced Esophagitis

Medications can cause esophageal injury resulting in esophagitis. Risk factors associated with pill-induced esophagitis include decreased salivary output, esophageal dysmotility, large pills, medications that increase the LES tone (opioids), and ingestion of medications in the supine position. Patients commonly report chest pain, dysphagia, and odynophagia occurring several hours to days after taking medication. Pill-induced esophagitis has been observed with alendronate, quinidine, tetracycline, doxycycline, potassium chloride, ferrous sulfate, and mexiletine. Medications associated with stricture formation include alendronate, ferrous sulfate, NSAIDs, and potassium chloride. Preventive strategies include drinking sufficient water with medication and remaining in an upright position for 30 minutes after pill ingestion.

Esophageal Motility Disorders

The esophagus is a muscle that passes a food bolus from the hypopharynx to the stomach through peristalsis. The upper third of the esophagus is composed of skeletal muscle innervated by axons of lower motoneurons. The lower two thirds is smooth muscle innervated by the vagus nerve. The upper and lower esophageal sphincters relax during swallowing.

Additional peristaltic activity occurs when the esophagus is distended. High-resolution esophageal manometry is used to evaluate suspected esophageal motility disorders.

GERD is the most common cause of noncardiac chest pain. However, hypercontractile disorders of the esophagus should also be considered in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Esophageal manometry is used to differentiate these disorders.

Hypertonic Motility Disorders

Hypertonic motility disorders are characterized by dysphagia with both liquids and solids. Other symptoms can include regurgitation of undigested food, in particular when in a recumbent position. Treatment of hypertonic disorders of the esophagus is aimed at relieving symptoms.

Achalasia and pseudoachalasia

Diffuse Esophageal Spasm and Nutcracker Esophagus

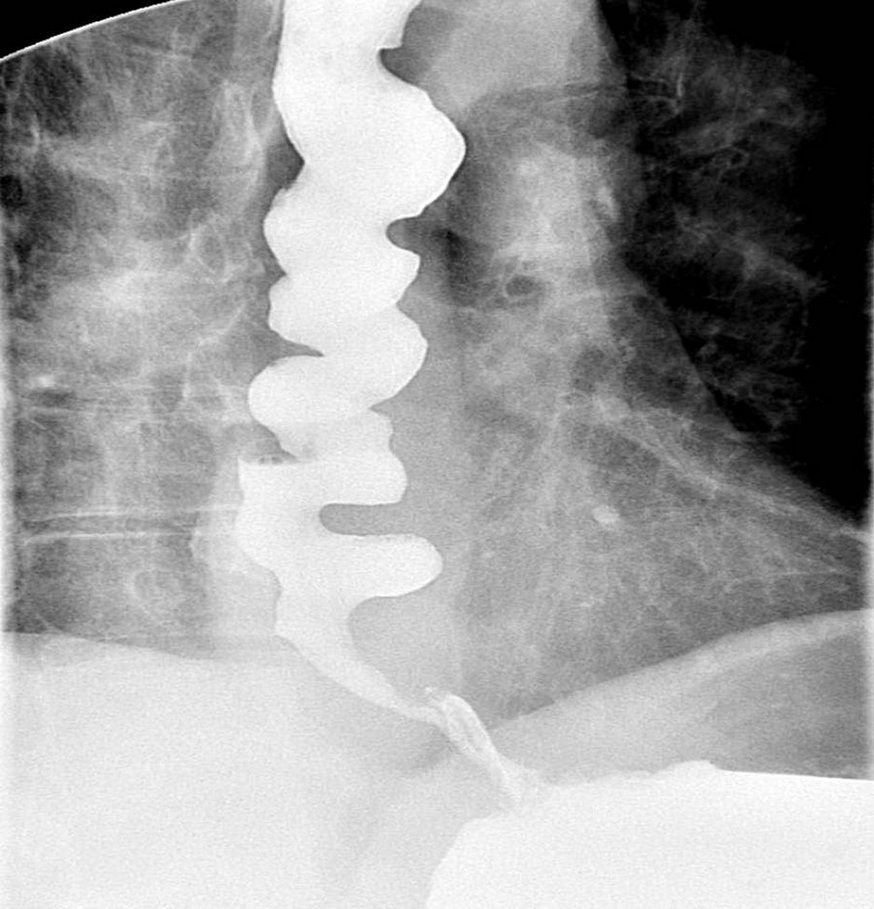

Diffuse esophageal spasm is a hypercontractile state presenting with chest pain or dysphagia. Symptoms often respond to nitroglycerin, suggesting a flaw in esophageal nitric-oxide production. The esophagus has a “corkscrew” (Figure 6) or “rosary bead” appearance on esophagography. Esophageal manometry shows simultaneous high-amplitude (>30 mm Hg) esophageal contractions with intermittent aperistaltic contractions. Medical therapy with antidepressants (trazadone and imipramine) or a phosphodiesterase inhibitor (sildenafil) can relieve chest pain. Dysphagia may respond to calcium channel blockers. Botulinum toxin injection has been reported to alleviate dysphagia symptoms.

Findings of a “corkscrew esophagus” (caused by multiple simultaneous contractions) on esophagography are typical of diffuse esophageal spasm.

Findings of a “corkscrew esophagus” (caused by multiple simultaneous contractions) on esophagography are typical of diffuse esophageal spasm.

“Nutcracker” or “jackhammer” esophagus is found in patients with high-amplitude peristaltic contractions of greater than 220 mm Hg.

Hypotonic Motility Disorders

Hypotonic disorders of the esophagus are marked by lack of contractility and incomplete peristalsis. Patients may report symptoms of GERD, which result from decreased LES pressure or dysphagia from incomplete peristalsis. In most cases, the cause of hypotonic esophageal disease is unknown. However, secondary causes include smooth-muscle relaxants, anticholinergic agents, estrogen, progesterone, connective tissue disorders (scleroderma), and pregnancy. Esophageal manometry shows hypotonic, weak nonperistaltic contractions in the distal esophagus. Findings can mimic achalasia.

Treatment includes lifestyle changes, such as eating upright and eating liquid or semisolid rather than solid food. Medical therapy includes acid-reducing agents for GERD and low-dose antidepressants to reduce chest discomfort. Prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide, are not recommended for treatment.

Metaplastic and Neoplastic Disorders of the Esophagus

Barrett Esophagus

Epidemiology and Screening

Barrett esophagus is defined as the extension of the metaplastic columnar epithelium above the GEJ into the esophagus. Barrett esophagus is a consequence of GERD, even in patients who experience no clinical symptoms, and is classified as a premalignant condition because it has the potential to progress to esophageal cancer. Risk factors associated with Barrett esophagus include chronic GERD (for more than 5 years), age older than 50 years, male sex, White race, tobacco use, and obesity. Drinking alcohol is not associated with increased risk for Barrett esophagus, and wine consumption might be protective.

Risk factors associated with Barrett esophagus progression to dysplasia or esophageal cancer include older age, long Barrett esophagus length, obesity, and tobacco use. Some studies have suggested that the use of PPIs, NSAIDs, and statins may be protective; however, this has not been established, and the use of these agents solely for prevention of progression to dysplasia is not recommended. The annual cancer risk associated with Barrett esophagus without dysplasia is 0.2% to 0.5% per year. For Barrett esophagus with low-grade dysplasia, annual risk for cancer is 0.7% per year, and for Barrett esophagus with high-grade dysplasia, 7% per year.

About 10% of patients with GERD are found to have Barrett esophagus on endoscopy. Studies have suggested individuals with multiple risk factors for esophageal carcinoma and chronic GERD might benefit from screening. Men older than age 50 years with GERD symptoms for more than 5 years and additional risk factors (nocturnal reflux symptoms, hiatal hernia, elevated BMI, intra-abdominal distribution of body fat, tobacco use) may benefit from screening endoscopy. Women do not require routine endoscopic screening for Barrett esophagus. Evidence does not support routine screening for Barrett esophagus based on GERD symptoms for the general population.

Diagnosis and Management

The diagnosis of Barrett esophagus is established based on endoscopic findings (Figure 7) with biopsy, which are then confirmed by pathology showing specialized intestinal metaplasia with acid-mucin–containing goblet cells. Endoscopy measurements have categorized Barrett esophagus into short-segment (≤3 cm) or long-segment (>3 cm). The Prague classification more accurately assesses a segment of Barrett esophagus using the degree of circumferential disease (C followed by a number indicating the length in cm) along with maximal Barrett esophagus segment length (M followed by a number indicating the length in cm). For example, a patient with Barrett esophagus extending circumferentially for 2 cm above the squamocolumnar junction but with tongues of Barrett esophagus extending 5 cm above the squamocolumnar junction would have a Prague classification of C2M5.

Upper endoscopic view of Barrett mucosa, with salmon-colored mucosa representing Barrett mucosa compared with the normal pearl-colored squamous mucosa.

Upper endoscopic view of Barrett mucosa, with salmon-colored mucosa representing Barrett mucosa compared with the normal pearl-colored squamous mucosa.

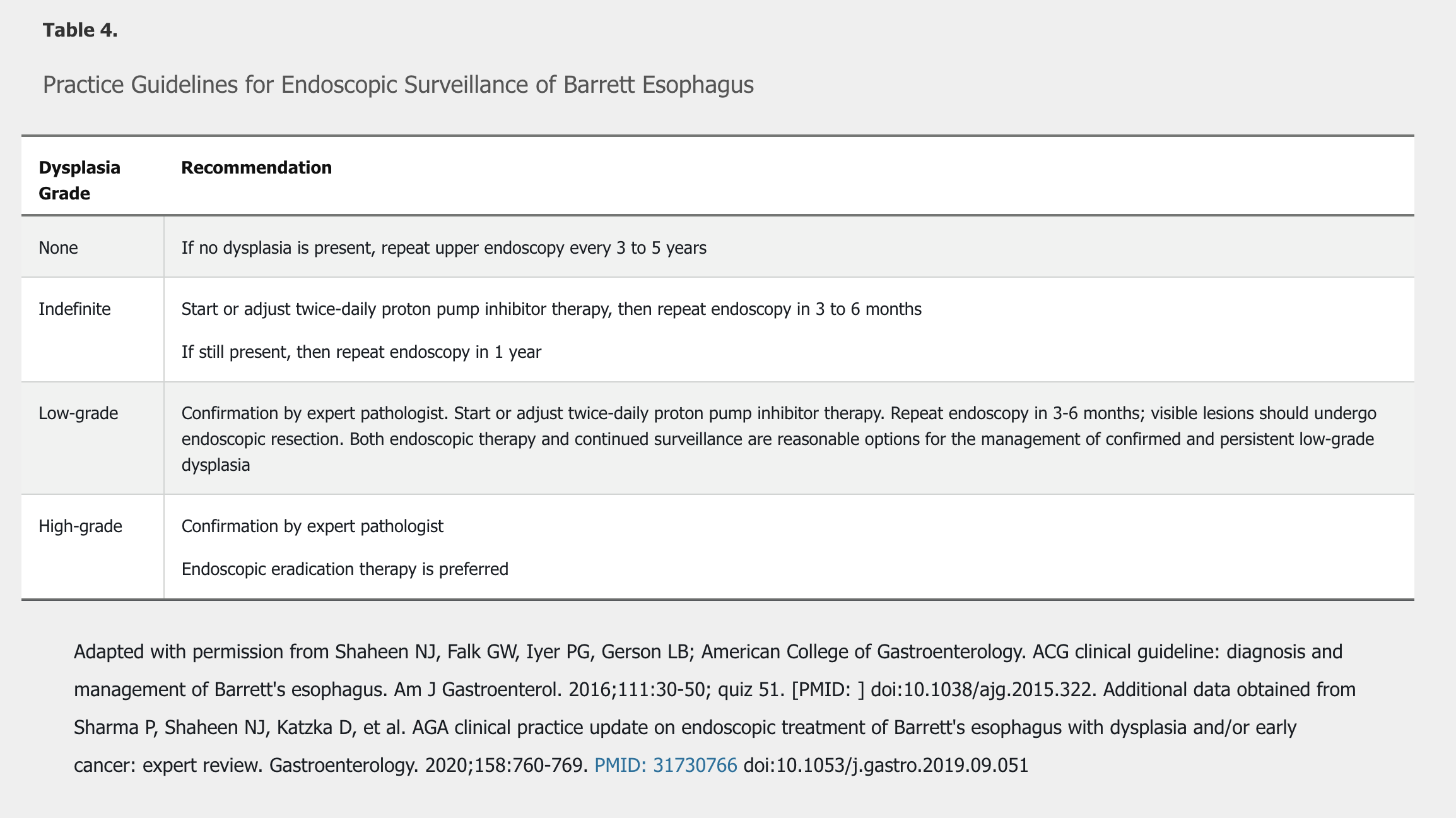

Barrett esophagus progresses along a pathway from intestinal metaplasia, to indefinite for dysplasia, to low-grade dysplasia, to high-grade dysplasia, to invasive adenocarcinoma. Surveillance and treatment recommendations are based on grade of Barrett esophagus and the presence of dysplasia (Table 4).

In patients with Barrett esophagus, medical therapy should be used to treat reflux symptoms and to heal reflux esophagitis. Initial dosing is once daily. There is no strong evidence that antireflux surgery can prevent the progression of Barrett esophagus to adenocarcinoma when compared to medical therapy with PPIs. NSAIDs and aspirin should not be prescribed as an antineoplastic strategy.

Patients with a diagnosis of Barrett esophagus indefinite for dysplasia should start or optimize PPI therapy to treat symptoms or heal esophagitis, followed by repeat upper endoscopy. Treatment to remove Barrett esophagus is recommended for patients with high-grade dysplasia and confirmed low-grade dysplasia. Endoscopy-based therapies include radiofrequency ablation and endoscopic mucosal resection, possibly used in combination. Endoscopic therapies have had similar outcomes to surgery (esophagectomy) in patients with high-grade dysplasia, but local expertise and patient preference will determine the best course of therapy. The Prague classification is useful to more accurately assess response to endoscopic therapy.

Esophageal Carcinoma

Epidemiology

The incidence of esophageal cancer varies widely between regions of the world; high-prevalence areas include Asia and southern and eastern Africa. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma comprises about 90% of all esophageal cancers, but incidence has been decreasing in Western countries as the incidence of adenocarcinoma is rising. Esophageal cancer occurs in the fifth to seventh decade of life and is three to four times more common in men. In the United States, about 16,000 new cases are reported annually, with 15,000 deaths occurring within the same year. The overall 5-year survival rate ranges from 15% to 25%, depending on the stage of the cancer at the time of initial presentation. The rate has remained relatively unchanged since 2000.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for the development of adenocarcinoma include GERD, Barrett esophagus, obesity, tobacco use, past thoracic radiation, a diet low in fruits and vegetables, older age, male sex, and the use of medications that relax the LES. Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma include tobacco and alcohol use, caustic injury, achalasia, past thoracic radiation, nutritional deficiencies (zinc, selenium), poor socioeconomic status, poor oral hygiene, nonepidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (an autosomal dominant disorder associated with yellow, wax-like hyperkeratosis on the palms and soles, also known as tylosis), human papillomavirus infection, and nitrosamine exposure.

Diagnosis and Staging

The most common initial presentation of esophageal carcinoma is dysphagia with solid foods, but asymptomatic individuals have been diagnosed based on surveillance endoscopy. Other symptoms include weight loss, anorexia, anemia (secondary to gastrointestinal bleeding), and chest pain. Upper endoscopy with biopsy is the preferred diagnostic test.

Squamous cell carcinoma is most commonly located in the proximal esophagus, and adenocarcinoma is usually found in the distal esophagus.

TNM staging is often done with endoscopic ultrasound for locoregional disease and with CT and PET to identify metastatic disease. For treatment of esophageal carcinoma, see MKSAP 18 Hematology and Oncology.